Exmouth & the Ningaloo Reef, Australia

While I’m in Australia, I’m working in the remote town of Exmouth. The landscape here is the classic red soil and small shrubbery that I picture when I think of Australia (largely based on films).

Exmouth is a popular tourist destination for a few reasons, but this time of year, tourists are usually here to see the reef. The Ningaloo Reef is a fringing reef located near Exmouth, and it draws a variety of megafauna (whales, sharks, manta rays, dolphins, turtles, etc) as a feeding ground along the migration route of many of these animals. Luckily, I am scheduled to spend most of my time here in the water, but instead of looking for large animals, we are looking for small Irukandji jellyfish.

This jellyfish is part of the box jellyfish group, which are typically known for their powerful stings. Irukandji jellyfish stings cause Irukandji syndrome in beachgoers and recreational boaters that are stung, the symptoms of which include full-body pain and an ‘impending sense of doom’. In a few cases, these stings have been fatal, especially for those that have underlying heart conditions. I actually had to get an ECG and be checked by my physician before I was cleared for field work.

While I’m here, I’m participating in a project led by PhD student Jessica Strickland. Her two supervisors are Prof. Kylie Pitt Griffith University, and Prof. Michael Kingsford from James Cook University. The project is supported by the Minderoo Foundation, who provides vessels, accommodation and lab space for us. The project will also provide important information for the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation, and Attractions (DBCA), who manages the whale shark and humpback whale swimming industries locally, and who will use outcomes of this project to inform public safety. This is the third and final season of field work for this project, and they recruited a few lucky volunteers to help with the sampling, including me.

A typical sampling day happens from the boat. Since jellyfish are not strong swimmers, they are carried by currents and tides. When two of these water features meet, they can cancel each other out and create a ‘slick’ that is visible from the surface.

Within the slick, there is often a cloud of jellyfish (about half a dozen species), Sargassum seaweed floating at the surface, and/or the fish and invertebrates that are known to associate with these Sargassum rafts. Despite being in the open blue water that is relatively empty, these slicks can house many plants and animals, including Irukandji.

[A cloud of small jellyfish is visible in the photo]Once we locate a slick, two swimmers put on their stinger suits, gloves, hoods and snorkelling gear, and swim a long transect with a camera. Later, Jess counts the number of Irukandji in the videos to get an idea of their abundance and density. She also compares these to videos from outside of the slick to test whether there are more jellyfish within the slick.

After the video transects, we collect live Irukandji and water samples. Jess is also trying to test the use of environmental DNA (eDNA), which is the DNA that is shed by plants and animals when they move through the water (scales, slime, you name it!).

The live Irukandji and water samples from the field are helping her test the method in the lab. Eventually, the water samples will help Jess understand the seasonal dynamics, spatial patterns of the Irukandji, and environmental factors (wind, temperature) that might result in changes year-to-year.

A typical sampling day is not complete without a cool sighting. Given that we are in their habitat, many animals are curious to know why we are splashing around at the surface, and they’ll come check us out once in a while. This almost always includes sharks, sea snakes, turtles and manta rays. We even had a friendly whale shark check us out one day!

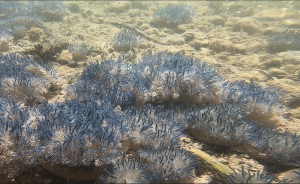

Side Project with the Upside Down Jellyfish

When the winds are strong and we can’t take the research vessel out, we take on some side projects! One of our side projects was sampling Cassiopea, the upside down jellyfish, that are found in a shallow pool near the beach. As the name suggests, these jellyfish are found with their bells against the ground and their tentacles facing up, because they are one of a few species of jellyfish that have photosynthetic symbionts – small plant friends that live in the tentacles and, in exchange for a place to live, they provide the jellyfish with some of the sugars they make. Corals are another group of animals with well-known symbionts, and jellyfish and corals are in the same phylum (Cnidaria), so they are closely related.